Image Details

Caption: Fig. 5.

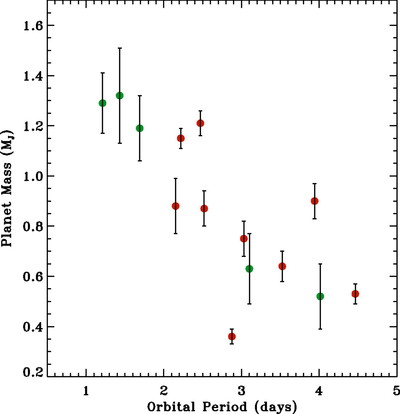

Left: Planet radius as a function of host mass for the 14 currently known transiting systems. Data are from Burrows et al. (2007 and references therein), except for TrES‐2 (this work). Green circles represent the distant OGLE sample, red circles indicate the sample of transiting objects found orbiting nearby (﹩d\lesssim 300﹩ pc) stars. Apart from two outliers, OGLE‐TR‐132b and HD 149026b, the correlation between these parameters appears clear in both the OGLE and the nearby samples of transiting giant planets. Right: Planet mass as a function of orbital period for the same sample, with the same color coding. Here the three OGLE planets with ﹩P< 2﹩ days drive the correlation (and no planets have been found yet in this period range by wide‐field transit surveys), which vanishes if the sample of nearby systems only is considered. It is still a matter of debate whether the lack of lower mass planets (﹩0.5\ M_{\mathrm{J}\,}\lesssim M_{p}\lesssim 1\ M_{\mathrm{J}\,}﹩) with ﹩P< 2﹩ days could be attributed to uncertainties in the determination of the stellar (and by inference, planetary) parameters for the faint hosts (e.g., Konacki et al. 2005; Santos et al. 2006; Pont et al. 2007), or whether it could be explained in terms of biases and/or selection effects (e.g., Gaudi et al. 2005a; Gaudi 2005, 2007; Gould et al. 2006). It is also possible there might be different upper‐mass limits in the two populations, for example from orbital migration and/or evaporation rate arguments (Mazeh et al. 2005; Gaudi et al. 2005).

Copyright and Terms & Conditions

© 2007. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A.